Designing and calculating values for snap fit

Snap fit design are small protuberance of plastic that flexes to clip and maintain two parts together. Computing these designs are difficult because of the numerous parameters to account for.

Here's a calculator that should make computing those easily.

Selecting the material to use

Please select the intended material to use from the table below. You can customize the characteristics if the defaults doesn't match your material.

Dumbest snap fit design

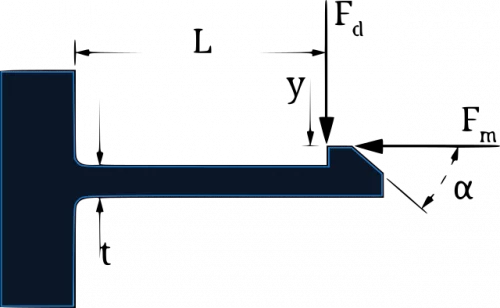

This is what's called the cantilever design. It looks like this:

A cantilever of a plastic material is bent while engaging in its matching part and a special hole in the matching part is created so it can relax in its unconstrained position when fit. Few tips for this design:

- The base of the lever should have fillet or chamfer to distribute its shearing forces on the mounting plane to the maximum possible area

- Ideally, the tip of the lever should be less wide than its base (it should look triangular), again to distribute forces correctly

- Never have the lever bent at rest

The parameters for this design are using this convention:

Maximum print speed from extrusion speed calculator

But how do you find the maximum extrusion speed for your hotend ?

The extrusion speed is the speed at which you can drive your extruder and still get consistent plastic output. Since it depends on the ability of your hotend to melt a given plastic volume, you'll need to create a 2 dimension matrix. On one axis, you'll write down the extruder speed and on the other you'll write down the hotend temperature. The value in each cell of the matrix is the amount of plastic you've extruded for the combinaison of (hotend temperature, extruder speed).

Usually, the higher the extruder speed, the more likely it'll fail to sustain the pressure required to extrude plastic out of the hotend, so it'll miss steps => extrude less plastic. By weighting the extruded plastic for each combination, you can figure out how well the extruder performed for such combination.

So:

- Send a

M83once to change to relative extrusion (so you don't have to accumulate your numbers) - Send a

M109 Rxxx(replacing xxx with the desired temperature to test). It'll only returnokwhen the hotend reached the temperature. - Clean your bed and make sure it's cold (you'll need to remove the extruder filament often, you don't want it to stick).

- Select a speed to test (for example

3mm/s, and convert it inmm/minby multiplying by 60 or use the calculator above). You'll then need to set the extrusion speed with aG1 Fxxx(replacing xxx by the speed you want to test). - Then you'll need to prime the nozzle by sending a

G1 E30 - (Optionally) you can pause the extrusion with

G1 F3followed byG1 E0.1 - Remove the drop of filament from the nozzle now.

- Reset the speed if you paused the extrusion with

G1 Fxxx(replacing xxx by the speed you want to test) - And extrude some filament

G1 E300(depending on your firmware, the extrusion length might be limited to250mmor less so adjust in consequence) - Capture the filament and weight it. You'll need a kitchen scale that's precise enough here.

If you perform the steps above for each combination of extrusion speed and temperature (you'll need to increase the temperature when you increase the extrusion speed, but don't go above to 260°C or 270°C for PLA) and report in an spreadsheet, you'll be able to observe and compare the limitation of the flow from the hotend. Typically, at a fixed temperature of 210°C, the quantity of extruded plastic will decrease when the extrusion speed increase. But if you increase the hotend temperature at the same time, you'll recover this loss up to a tuple.

This tuple (extrusion speed, temperature) will give you the maximum extrusion speed your hotend can support.

Then enter the extrusion speed in the calculator above and you'll find out the maximum print speed you can acheive.

This speed is theorical, since it's the case when the printer has finished accelerating (which needs space to perform), and the plastic has cooled enough to adhere but is not dripping on the last layer. With a 20% margin, you should be safe here.

Displacement

As the world is cruel, we have to obey nature's laws. Those laws state that a body can't change from one speed to an other speed instantly. It has to accelerate (or decelerate) to achieve this and this takes time. In our case here, we are interested mostly in the printer's X/Y movement (you are not usually limited by the Z movement speed, unless you are using a non usual firmware).

Depending on your printer's mechanics, the X or Y movement will be different, so it's not possible to provide a calculator that'd fit all printers. Instead, I'll try to explain few rules and you'll be able to compute the maximum acceleration your printer can achieve (and based on this information, the maximum speed).

For printers with direct axis control (no Core X/Y or H movement), with a screw or a belt, there is a direct relation between the rotation of the stepper motor and the displacement. You'll need to know the stepper motor steps per revolution and the screw or belt pitch (and number of teeth per revolution). Every revolution of the screw/belt lead to a progress of the carriage of one pitch of the screw (or X teeths of the belt).

Thus, the speed of the carriage depends on the number of steps per second a motor can sustain.

The speed is one thing, and the acceleration is another thing. There's no interest to a speed of 100mm/s if you need 2 days to accelerate to reach it.

To accelerate your carriage, you must also compute how much torque it can generate. This torques is used to fight against the torque required to hold the current position and overcome the resistance to movement (aka friction). For the former, it depends on your carriage visible mass and/or moment (depending on the mechanical configuration). The latter depends on how smooth the carriage can move. You'll lower resistance with a good lubrication for a screw, by changing the screw type (going to a ball screw for example), by changing the design so that the carriage is not supported by the scew but by bearing, roller, whatever, etc...

Since the above is hard to evaluate, it can be deduced by simple experiments:

- Prepare a G-Code file with square movement (move to one corner of the bed)

- Position the hotend above a dot on a paper (by manual movement)

- Move the hotend to another corner with a given speed (via

G0 X150 Y0 F1500, whereX=150, Y=0is the new position to reach (in mm),F1500is the feedrate, ie the speed to use (in mm/min)) - Move the hotend to another corner with the same speed (via

G0 X150 Y150 F1500) - Move the hotend to another corner with the same speed (via

G0 X0 Y150 F1500) - Move the hotend to another corner with the same speed (via

G0 X0 Y0 F1500) - If everything worked correctly, you should arrive on the same position (hotend on the dot you've drawn). Try again with increasing the feedrate until the motor starts to miss step (you'll see it does not reach the dot anymore), this is the maximum speed you can reach on large movement (so the acceleration shouldn't limit here).

- You can then reduce the amplitude of the motion (change 150 to 100 or less) and redo the tests above. At some point, the printer will max out the possible acceleration so you are more likely to miss steps. This will gives you the coherent maximum speed you can use (lower it by 10 or 20% to be on the safe side).

Cooling

While you've found the maximum extruder speed and maximum mechanical hotend speed, you must also ensure you're cooling the plastic fast enough that it does not deform anymore once extruded. I don't know the physical process enough here to provide a calculator. From an empirical observation, you can adjust the fan speed of the hotend (not the fan on the heatbreak part) from 0 to 255 and perform a temperature torture test. So, prepare a print with the maximum speed you can reach (that's the minimal of the maximum extrusion speed and the hotend speed) and print different pieces with different fan values.

You should run a dichotomic search here, that is:

- Run the fan at 0, and 255,

- If it's better at 0, try with 128

- If it's better at 128, try with 192 (else try with 64)

- And so on until you find the adequate cooling power you need for the plastic to solidify nicely