Making an expressive text to speech engine for French language

This article is a tutorial about how to make a state-of-art text to speech engine for a given language, typically French (but can be anything you want).

In the end of this article, you'll find an APK you can download and install on your Android smartphone that's implementing a TTS engine for French for, IMHO, the nicest voice you can find in the market.

What is a text to speech engine?

Said simply, a text to speech (latter: TTS) engine is a software that convert written text to an audio waveform containing the same text as spoken by a human.

This type of software is very old, and the quality improved over time. With the deep neuron network (often called AI) era, the final audio quality is now competing with a genuine human speaking the same text.

Basics of speaking and voice

Let's face it: we use our voice from day to day interaction, yet, we (mostly) have no idea how complex voice communication is.

From a morphology point of view, we modulate the sound we are generating with many organs (lungs, larynx, mouth, lips, tooth, noise), each having an impact on the produced sound. The generated sound isn't the same time wise, it's constantly evolving.

Since we are all different (biologically) the sounds you are producing are different from the sounds I'm producing, even if we both intend to speak the same text.

For most of us, it's almost impossible to mimic a speaker, so instead, most of the work is done in the hearing and parsing of the sound to decode what the initial intent was.

In a good TTS algorithm, we want that work to be as short and as easy as possible, so the generated sound should mimic the sound we are used to hear and process.

It would be possible to make a TTS algorithm that's only outputting perfect sine tones for each phoneme, but it'd be overly complex for a human to learn the scale and the meaning of this new language.

Instead, a TTS algorithm should mimic a human speaking the text as close as possible.

Researchers have set up a structure for spoken language, that's getting more and more complex depending on how profound you want to match the human process.

At primary school, you learn that there are vowels and consonants and it's enough, at this age, to match very basic sound to letters. However, the written text never follow the spoken language, thus some conversion is required to convert written text to human language (whatever the language).

So the second layer for this is using phonemes. Phonemes are small unit of sound a human can pronounce.

For example, when saying ta, you are using 2 phonemes, one for the explosive tee and one for the vowel a.

Notice that not all human are able to pronounce all phonemes. Some languages use phoneme other languages don't and it's hard for native speaker of those languages to even hear the phoneme. They'll hear the sound, but be unable to parse it.

In short, you'll usually say it sounds the same as, or I can't hear it (which, in reality, you can, but you can't understand/distinguish it).

For each phoneme, an international alphabet was created, it's called IPA (for international phonetic alphabet).

One could think that concatenating phonemes (that is, glueing phonemes together one after the other) would be enough to generate speech, but it's not the case. This create distorted (but comprehensible) audio that doesn't match what a human could do. Since humans are generating sounds with their organs, the shape and limitation of their actuators prevent them from creating perfect "phonemes". Each phoneme depends on the surrounding phonemes in a utterance.

Think of it as how hard it would be for your mouth to close and open, your lip to stand and to lay flat, you larynx to change pitch, and so on if you were to do it at the frequency of the produced sound.

Instead, the sound of a generated phoneme will be different depending on the previous phonemes you've already pronounced or you're about to pronounce.

Different sounds are generated, but the listener will parse them as the same phoneme. Worst, if the same sound were generated, the listener would find the voice unnatural

Then, enters the morphology of speakers into account. Even when the phonemes are correctly generated, based on the surrounding phonemes, there are sounds that a human organ can not create (or hardly) and thus, another sound is generated instead. We are speaking of where the sound is formed and shaped and we call this formants. A male and a female won't have the same formants and thus, even if you were to tune the sound produced by a male to the pitch of a female, the formant won't match and the generated voice will not sound natural.

When a male increase the pitch of his voice, he isn't making a female voice, not even a child voice, but a "chipmunk" effect

Reproducing the biological sound generation is usually called a vocoder (for voice coder).

History of TTS engines

Well, I'm not exhaustive here, so this paragraph would be full of inaccuracies for historical date if I included any date in there. Any date and technology in the listing below is approximate, but it's a good read anyway to understand what the human mind is doing when solving a problem.

| Algorithm type | Description | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Phoneme concat | The first TTS algorithms (I think it was SAM) simply concatenated phonemes. | It produced very hard to understand speech |

| Phoneme selection + Formant synthesis | Some rules were added to switch the phonemes based on their position in the generated phonetic text. Formants were also simulated. | This produced robotic, but intelligible speech |

| Diphones | Another idea come out of using phonemes pairs (or diphone) since it would be closer to our biological models. | This improved the understandability, but still, the voice was too repeatable, and synthetic |

| Unit selection | Why limit to diphone, if you can cut parts of speech in a given speaker and concatenate them rightly, it would sound perfect, right? This implied many more units and selecting the right unit was a challenge (usually solved by a hidden Markov model, the ancestor of DNN). | The generated voice started to sound natural, albeit, without any soul, or expressiveness. |

| Deep neural networks | In short, trash everything we've done earlier and let a neural net learns the pattern by itself. | The voice are completely natural, most of the time, expressive but sometime gibberish voice is generated when the network is hallucinating. |

What is the business model for TTS ?

Up until unit selection era, TTS wasn't good enough to use for everyday usage. It was a convenience for disabled persons so they could use a computer, albeit, slower and usually with a lot of difficulties. Said shortly, there was no actual valuable market for TTS.

When unit selection engines came out, the quality was starting to be good enough for some usage, where it would make an economical sense to avoid paying a person to pronounce text and have a computer doing so. It still wasn't the SaaS era yet, so company were selling their software and consumer could produce as much utterance as they want. The entry price was high, but not too high

It's about when Android started to include a TTS engine by default, using an open source (but closed model) SVox engine.

Then engines started to improve better and the voices started to detect "feelings" or "intention" in the spoken text. The expressive TTS engines started to be sold for more usage, like true text to speech feature. It was possible, by then, to buy another TTS engine on one smartphone, and have text to speech service running on a smartphone (for ebook reading, for navigation, and so on).

That's about when the TTS engine publisher started to realize that the TTS market isn't big enough for the ever ending new competitors' wave. A consumer with a working (let's say good but not perfect) engine will not buy another engine. Says shortly, their business was dead ended.

So they invented SaaS (speech as a service): The idea is to have the consumer pay per utterance generated. That way, they have a recurring business income and they can continue to develop new and better engines. However, large text conversion would become extremely expensive, rendering the whole process unaffordable for ebook reading (for example).

The DNN engines started to produce good results. Thus, the GAFAM stepped in the market. Google installed a default TTS engine on Android phones that was good enough for navigation purpose (understand: pronouncing the street names). It was a closed source TTS engine, with closed model (but free for Android phone owners). It wasn't good enough for long text reading (unless you are very tolerant to errors and uncanny sequences).

Microsoft added a Bing Speech API that was free to use (using closed source and closed model). The original TTS engine manufacturer's business was dead, since even if they had better engine, their fame was lower than Microsoft or Google, it was hard to find them in search engine results, game over.

Yet, even the Google or Microsoft TTS engine have defects. The first (and biggest) is that you need to be connected to a network to query their server, wait for generation of the spoken text (which, even with their giant server farm, still takes time due to the number of clients to serve). Google solution was running on device, but the quality is lower than Microsoft's online version. Embedded engine using DNN takes a lot more resources than unit selection engines (we are talking about 2 orders of magnitude more resources).

Paradoxically, it was very difficult for a third party to create a good TTS engine with unit selection from scratch, yet, it's way easier to do with DNN, since the DNN engines architecture is often documented (although the weights of the network aren't public). The secret sauce of rules to produce a good unit selection engine was secret.

Open source (and open weight)

While the sharks were swimming in the pool, few good minded people tried to implement TTS engine openly. Initiatives came from scholars, and university mainly.

There are few gems from them, like MBROLA, and Espeak. (And many other, but listing them here would be too long).

The latter does the heavy work of converting written text to phonemes with all the unexceptional exceptions to text-to-sound rules in each languages. Getting unit selection to work implied many hard to perform test and understanding hard to master HMM, so even if text-to-phoneme was an almost solved problem, phonemes-to-speech wasn't.

Then entered DNN engines and it was now possible not to grasp the intrinsics of the statistics and yet get a working result (the main advantage of a deep neural network is to simply let it find the solution by itself, even if you absolutely don't understand how it'll do it).

Starting with the AI wave, it's now possible for an individual to create a working and excellent TTS engine from scratch without any resources (or not any unusual resources)

I'm not listing here all the TTS engine with DNN that were published as either open weight or open source.

The latter are much more rare than the former, but much more useful, since they describe how they trained their model and allow any developer to do the same.

Making a TTS engine for a (new) language

After this lengthy introduction, let's get to the meat of this article, how do we make a TTS engine for our preferred language?

First, bibliography (I'll spare you this part). I'm already found the best engine at the time of writing this article, and I've elected MatchaTTS.

The main reason for this choice is that the paper is clear and easily understandable.

Even if you don't read it, the provided open source code includes everything needed to bootstrap and reproduce the resulting model (which, believe me, if so rare that it must be emphasized).

The other reason is that this software builds on top of the shoulders of giants, instead of reinventing the wheels. Typically, it's using espeak-ng for text-to-phoneme conversion, instead of trying to get that part done by a DNN.

To explain why it's a best idea here, think about the hidden rules we take for granted when writing text and reading it. For example, you're paying your taxes, so you'll write $11203.45 in some form.

When a TTS engine finds this text, it can either pronounce each digit individually (and it's impossible to understand) or it can stack them two by two (again, impossible to understand). It can't make a difference between the dot . in the number to the dot at the end of this sentence. Why should it pronounce the former dot and just make silence for the latter?

Yet, what a human expect is something like eleven thousand two hundred three dollars and forty five cents, which is completely different to what's written.

And notice that there is not a single valid solution for this conversion. Imagine the same thing for 9/14. If it's a date, the text to pronounce is September the forteenth, if it's a ratio nine forteenth and so on. If it's a list of number nine forteen, if it's a code nine slash forteen and so on.

What should the algorithm do, when it finds the king's fiancée?

Ignore the accent and pronounce as phyancee ? Learn French, and pronounce as it's written ? Should it learn all languages because we're sharing words between languages ?

A DNN engine that doing the work for text-to-phoneme would have to be huge to learn all the rules to convert (and not make any mistake) text to phoneme.

DNN are huge parrots. They learns to reproduce what's being shown to them. So even if you've thought them to convert the number 12345, they don't know how to convert 13345. They are dumb and don't infer the rules here. Thus, it would requires a gigantic dataset to see and learn all the rules.

Yet, these rules are simple enough to make a "dumb" (and deterministic) algorithm do that beforehand (or simply use a dictionary when it makes sense) . Don't forget that each task we are delegating to a DNN means a lot of power is burnt for the task. If you can spend your power budget cleverly, you're winning in the end.

That simple algorithm is what Espeak is doing. It relieve the work of phonemes-to-speech to the network, it's doing the text-to-phonemes work and it's doing it very fast and well enough.

Even the phonemes-to-speech can be simplified into two steps, a first step being phonemes-to-spectrogram and a second step from spectrogram-to-audio. The reason here is that creating spectrogram (actually, mel spectrogram which are a bit like 2D images) from text is a well know domain for DNN. Then the latter step, converting the real 2D spectrum to temporal 1D signal is usually done by a vocoder (again, a well known domain for DNN).

MatchaTTS's DNN work is only doing the phonemes-to-spectrogram job. Once you have the MEL Spectrogram, a standard vocoder is used (like Hifigan, Vocos or even Griffin-Lim) to generate an audio wave.

This approach is different from other open source TTS engine and I've selected it because it's simple to understand and debug. The lower level the DNN usage, the better for understanding what it's doing.

Cooking recipe

First let's give the credits where they are due:

- espeak was started by Jonathan Duddington

- espeak-ng is a fork of espeak

- MatchaTTS is a code from Shivam Mehta, Ruibo Tu, Jonas Beskow, Éva Székely, and Gustav Eje Henter

- A finetuning tutorial that helped me understand the code structure

- SherpaOnnx for the Onnx runtime and Android's TTS Engine example code.

- My branch of MatchaTTS that's already prepared for french

Ingredients

- A computer with a NVidia GPU. A RTX2060, 6GB VRAM is enough, you don't need high end card. I was able to start training on a AMD RX card, but it was way too slow to be usable.

- The computer should have a usable operating system. I'm using Arch linux, but it works with Ubuntu 24.04 too, since the required dependencies are old.

- A dataset of audio utterance and their matching text (more on this later on)

- Some disk space (40GB is a minimum for the temporary files)

- Python 3.10 (if you don't have this version, you'll encounter errors later on)

- Usual build dependencies (g++, python, git, cmake, ...)

- Android studio (for generating the APK)

Preparing the code

Clone all the given repositories above.

Typically, use git clone --branch french https://github.com/X-Ryl669/Matcha-TTS.git

You need to create a virtual environment for python, with python3.10 -m venv .venv, followed by . .venv/bin/activate

Then install all the required dependencies: pip install -e .

Make sure you're installing pytorch with a version that's smaller than 2.8.0, since there are changes in the latest version that breaks existing code (ah, python, python...). For example, you can do pip install --force torch==2.1.0 torchaudio==2.1.0 torchvision==0.16.0 markupsafe==2.1.1 numpy==1.26.4 pillow==10.4.0

You don't care if it reports issue with gradio, it's not used in the process anyway.

Dataset

The success of a TTS engine using DNN depends 120% on the quality of the dataset. I'm listing below what is a bad dataset:

- Multiple speaker dataset (like Librispeech, Mozilla Common Voice, ...). This is bad because it forces the network to learn an average model from all speakers but an average model of larynx/mouth/nose/... doesn't exist and would sound horrible if it happened. Maybe with a huge network that's able to separate the speakers independently it could work, but MatchaTTS network doesn't expect this.

- Audio that's recorded with laptop microphone or so. Even if you sorted and extracted a single speaker from those multi-speaker dataset, most of those recording are done with a laptop microphone, with a lot of noise and a very funky spectral response. The model will learn these defects and no matter how good you'll postprocess the files, they will sound like garbage.

- A varying prosody. If, for example, your dataset contains poems or theater play or any sort of acting, the model will learn and apply the acting in unexpected places in its generation. I made a TTS model that's specialized for speaking poems, and it's awful for ebook reading. You want a flat and consistent prosody for your model. Again, MatchaTTS doesn't learn "tags" you could embed in the text, so avoid those.

- A short dataset. Even if your dataset is perfect (smooth prosody, good audio quality), you need many material for it to learn all the "units", that is the combination of phonemes. At least one hour is required, but you'll get better result with 3 to 6 hours of text, or around 5000 to 10'000 sentences.

- A bad matching of audio to text. I've used parakeet to convert audio to text (automatic speech recognition) and although the ASR results are good, they are not perfect. They don't include exclamation or question marks, comma, dots and so on. They sometimes miss words or worst, add inexistent words. I matched (automatically, at first then manually for failed automatic matching) the expected text from the ASR extracted text and fixed the error. That took 2 weeks of work for 10'000 sentences.

- A wrong balance of questions and exclamations in your model. I can't tell what is the good ratio of questions to exclamation to normal sentences. If you don't have enough questions, the model will not reproduce the expected increase in pitch at the end of a question. I have around 10% questions and 15% exclamations in my dataset. I'm still wondering if having long pauses after a dot-end-of-sentence is better for prosody or not. I've added artificial 0.7s of silence for sentences ending with a

.and will evaluate if I like this better or not. - No repeat in your dataset. If you don't have repeating sentences (that is, sentences that are written the same, but are pronounced slightly differently), then the model will typically learn a single pronunciation and will sound more "robotic". Human speech is always different, even if you always say the same thing.

I'm not sharing the dataset I've used to train my model, since it implies audio files that I don't want to distribute.

Preparing the dataset You're likely to use a long recording of text from a voice that sounds good. You'll need to split this recording in small utterance (even smaller than sentence, can be single words). You need a good distribution of small to large sentences. You can use automatic tools for that, like this site is doing. If you can't find a noiseless recording, you can try this tool for cleaning it. It'll sound less garbage, but still far from what you can get from a clean recording at first.

If you have the transcription of the spoken text, it's better. If you don't, you'll need to provide this yourself (and it's a long an tedious work). Don't use automatic tool to transcribe, else their errors will be the final model. Often, in the transcription, you'll find errors too, so double checking the written text for the spoken text is required. Yes it's long, but it's unavoidable.

I've split the dataset in chapters and chapters in utterance (an utterance can be a single word, a subpart of a sentence, a sentence or 2 sentences).

For each utterance, I've a line in a CSV file that contains the path to the utterance WAV file, and its transcription, separated by a | (pipe) character

It looks like this:

Dataset/ch01/01-001.wav|Le soleil est tombé

Dataset/ch01/01-002.wav|Non?

Dataset/ch01/01-003.wav|comment il fait, je ne le sais point

[...]I've stored my dataset in the Dataset folder, and the scripts below use that, so it's better if you do the same.

Resample all wav file to 22050Hz and trim silence from both end, except if it ends with a . (in that case, ensure it has, at least 0.5s of silence in the end)

I'm using sox tool for this, typical usage is:

$ sox input.wav tmp.wav rate 22050

$ sox tmp.wav output.wav silence 1 0.1 0.1% reverse silence 1 0.1 0.1% reverse pad 0 0.7Make a script for calling this on all your files.

Extracting the IPA alphabet used for your language The process for training is like this:

- Convert the text of some sample utterance in the dataset to its phonemes (using IPA alphabet)

- Train using the phonemes to MEL spectrogram

Since it's a network, the input vector for each phoneme is an number, that is: an index in a list of possible phonemes. The possible phonemes are called symbols in MatchaTTS and you need to specify those used in your language. I've extracted the list of phonemes used in French online (I don't remember the source). I haven't removed those in the original MatchaTTS source code (only added the other one), since I think there are often English words in French, so it's likely that phonemes that could be specific to English will appear in a French text. I'm not 100% sure it's the case, but it works.

The file to look for is in matcha/text/symbols.py. Adapt to your need.

If you intend to export an ONNX model for sherpa later on, append ^$ to the end of line that reads

"ɑãẽõɐɒæɓʙβɔɕçɗɖðʤəɘɚɛɜɝɞɟʄɡɠɢʛɦɧħɥʜɨɪʝɭɬɫɮʟɱɯɰŋɳɲɴøɵɸθœɶʘɹɺɾɻʀʁɽʂʃʈʧʉʊʋⱱʌɣɤʍχʎʏʑʐʒʔʡʕʢǀǁǂǃˈˌːˑʼʴʰʱʲʷˠˤ˞↓↑→↗↘ᵻ ̃"since SherpaOnnx uses these 2 symbols for detecting beginning and end of sentences. If you forget it's not important, you'll be able to fix that later on.

Export your symbols in a tokens.txt file. This can be done easily via running python and typing:

import text.symbols

f = open("tokens.txt", "w")

i = 0

for s in text.symbols:

f.write(f("{s} {i}\n")

i = i +1

f.close()Exit with Ctrl + D

Split the dataset in 3 sets

For training you need a train.txt file that contains the majority of the dataset, a test.txt that contains the some random sample rows of your dataset for testing the efficiency of the model and a val.txt containing other random rows of the dataset, used to validate an epoch performance.

Doing this by hand is tedious, so a script called split_metadata.py is included in my repository to do this. You'll need to edit it to set the path to your dataset path.

Computing the statistics for your dataset

I'm reproducing the advice here. If you have kept the dataset in the Dataset folder and used split_metadata.py correctly, you can keep what I've set in the custom yaml files found in configs/data/custom.yaml.

You'll need to compute normalization statistics of the dataset by running: ./matcha-tts-env/bin/matcha-data-stats -i custom.yaml -f

That'll output something like:

Output: {'mel_mean': -7.081411, 'mel_std': 3.500973}Update these values in configs/data/custom.yaml under data_statistics key.

Preparing for training

One more step before the big one. You'll need to tell Matcha what language your dataset is in.

The easiest solution is to edit this file matcha/text/cleaners.py and change the line 152 that contains "fr" to the language code you are using (in espeak terms). Don't rename the function, it's useless.

So for Spanish, you'll use "es" instead.

Also change line 28.

For Spanish, change language="fr-fr", to language="es-es"

Train!

Once everything is set up, simply run:

python matcha/train.py experiment=customAnd wait for the progress bar to appear.

Then wait until a complete epoch computes. It'll likely fail with an Out-of-memory error if the batch size is too big for your GPU.

In that case, you'll likely need to adjust the batch size (defined in the file configs/data/custom.yaml) to a smaller value. A 6GB GPU will work with a batch size up to 9. A 8GB GPU supports up to 26 and so on. Experiment with different values until it works.

By default, a checkpoint will be saved for each 100 epochs (that's approximately 100'000 steps).

If you had to interrupt the training and want to resume it, you can rerun the line like this python matcha/train.py experiment=custom ckpt_path=logs/train/custom/runs/DATE_HERE/checkpoints/last.ckpt

If you're doing training on a remote computer, you should run the line above in a screen or tmux console, so it doesn't get killed if you log out of the terminal by error

Concerning training, by default Matcha creates a tensorboard compatible file, so you can monitor its progress by starting it.

Open another terminal and go to logs/train/custom/runs/DATE_HERE/tensorboard and run tensorboard --logdir=. --bind_all --port=6007

Open your browser on http://localhost:6007 to get the interface to show up.

As for "how much training should I do?" question, here are my numbers.

After few epochs, the loss/train_epoch metrics quickly drops from 3.5 to ~2.4 value. Until the model is below 2.4, it's not good enough (IMHO). I'm reaching below 2.4 after ~100k steps and 2.34 after 400k steps. The sub_loss/train_diff_loss_epoch become good when it's below 1.2 (for me), which happens in the 300k steps range. I don't remember why, but the first training I've done, I had 100 epoch with 80k steps but now my epochs are 1000 steps or so. I think it depends on batch size.

Once you have a checkpoint, you can test your model with this code:

matcha-tts --cpu --text "Your text here" --checkpoint_path ./logs/train/custom/DATE_HERE/checkpoints/last.ckpt --vocoder hifigan_univ_v1This will create a utterance.wav file that contains the first sentence of your text.

Exporting your model

Then you can export your model to onnx. For this to happen you'll need to fetch few more packages:

pip install --force torch==2.1.0 torchaudio==2.1.0 torchvision==0.16.0 markupsafe==2.1.1 numpy==1.26.4 pillow==10.4.0 onnx onnx-ir onnx-scriptThen export to onnx like this:

python -m matcha.onnx.export ./logs/train/custom/DATE_HERE/checkpoints/last.ckpt.ckpt model.onnx --n-timesteps 3The last element should be 2 or 3 (better quality, but more processing required for inference). Honestly, even 2 is very good.

And append metadata to the onnx file. Edit file add_metadata_onnx.py for your language, name and so on, then run:

python add_metadata_onnx.py model.onnxImport in SherpaONNX for making an Android application

Clone the K2Sherpa repository and follow this guide

You're looking for the project SherpaOnnxTtsEngine (not SherpaOnnx as specified in the documentation above)

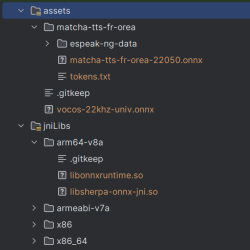

Then copy the model.onnx to /path/to/Sherpa/android/SherpaOnnxTtsEngine/app/src/main/assets/yourmodel folder.

You'll need to copy the file vocos.onnx to /path/to/Sherpa/android/SherpaOnnxTtsEngine/app/src/main/assets/ (you'll find this file in the release page of K2Sherpa, or in this archive)

You'll need to edit the source code as specified in the comment of TtsEngine.kt and get a few build done and fixing until it works as expected.

Typically, look at line 66 and after:

// For Matcha -- begin

acousticModelName = "matcha-tts-fr-orea-22050.onnx"

vocoder = "vocos-22khz-univ.onnx"

// For Matcha -- end

// For Kokoro -- begin

voices = null

// For Kokoro -- end

modelDir = "matcha-tts-fr-orea"

ruleFsts = null

ruleFars = null

lexicon = null

dataDir = "matcha-tts-fr-orea/espeak-ng-data"

lang = "fra"

lang2 = nullThe final tree should be like this:

Link to final APK

You can download the generated expressive voice here